As fears around mortgage stress grow, and interest rates remaining stagnant for the foreseeable future, some form of macroeconomic regulation is on its way - prospective borrowers should be prepared.

The Issue

With interest rates at record lows, asset prices growing and borrowing capacities being stretched, there are real fears that households are having to stretch their borrowing levels beyond reasonable and sustainable limits.

The Bank for International Settlements that collates data for debt levels around the world stated that "Australian household debt is equal to 123.4% of our GDP, the highest of any country except Switzerland.”

This is a challenge not limited to Australia, but also to other countries around the world. New Zealand is one example, with annual price rises on residential property approaching 30% in the last 12 months.

And locally, borrowing levels are growing as a result as the ABS data shows.

Unlike the post GFC period (2009-2011), generally it is the owner occupier/sea changers that are outbidding the investor market this time.

The obvious outcome is that despite the low interest rates, households are having to borrow a lot more that they would like to. Yes, you can borrow at 3% not 5%; but if you are having to borrowing an extra $250,000 it will be a lot more expensive in the long run.

According to Australian Prudential Regulation Authority ("APRA") data, the number of new residential mortgage loans where debt is at least 6 times greater than income, is now up to 22% of new loans (increase from 16% a year earlier).

Is regulating markets an option?

There are different levers of course for any society to influence economic outcomes. You can either regulate behaviour via the blunt instrument of law, or let the markets find the right balance.

In truth, history tell us that some combination of both tools is necessary. Though currently, "market forces" in the form of increasing the cost of debt is not available to us at this time. If rates were to increase by say 1.0% - 1.5% much of the work in moderating the current property price growth would be done by markets. In most cases and economies, this is the most efficent method of setting the standards.

Why can't interest rates go up?

Naturally these is some complexity to this, and any commentary around this is sweeping over many of the macro issues.

We could talk of upward forces, including inflation readings beginning to show a heartbeat for the first time in years, central banks around the world wanting to end stimulus, along with positive vaccinations rates.

Offsetting this is the need to support employment, including to support the levels of household debt. For example, Australian households may struggle with a jump in interest rates, particularly if wages growth remains stagnant.

The bigger factor is our exchange rates, and in some respects it is the a race to the bottom with all countries wanting to maintain a "competitive" currency position. Higher local interest rates attract foreign demand for bonds etc. and upward pressure on our dollar.

What does regulation look like?

Certainly everyone is having a say at the moment, firstly the International Monetary Fund ("IMF"), the Federal Government, the RBA and APRA.

The Federal Treasurer refers to "macroprudential settings" and this impacts the rules that APRA may set for the financial institutions it oversees.

It is quite ironic that the very problem regulators have been trying to solve in the past (housing affordability) is in part now contributing to the issues we face today. Anyway.

If we go back to 2017 when macro regulation was last applied, APRA specifically targeted the property investor segment was driving the market.

The measures included a 10% cap on annual investor lending growth, along with a 30 per cent cap on new interest-only lending as a proportion of all new home loans. This was also supported by increased floor rates for assessing loan servicing.

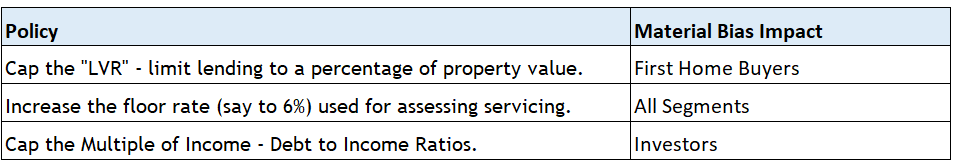

So this time around, the broad options include:

Of the "new" options, the Loan to Value Ratio (LVR) cap is one that has been used in other countries, which is obvious biased towards the segment of the market that has less equity or deposit available to put down. First Home Buyers would be most materially impacted here.

None of the approaches are perfect, and none have the same effect on the psyche of the borrower compared with actually increasing interest rates.

The likely scenario

The IMF noted that regulation could take the form of "increasing interest serviceability buffers and instituting portfolio restrictions on debt-to-income and loan-to-value ratios."

It seems likely that APRA will target Debt-to-Income Ratios or DTI's, probably by limiting the proportion of lending that can be approved above say 6 times an applicant's household income.

DTI simply divides Total Debt by Total Gross Income, and ignores the cost or term of debt, and provides a more draconian measure of credit worthiness. For more information on DTI's visit our previous blog.

If anything is to be done, simplicity is a good thing, and perhaps it then becomes an opportunity to establish a clearer definition of borrowing capacity across households. A little more fiancial literacy is never a bad thing.

More Information?

E: enquiry@mcpgroup.com.au

W: www.mcpfinancial.com.au